The Skin

The following information is regarding the

structure and function of the skin, including the appendage structures

derived from the skin (hairs and nails) and structures below the

surface of the skin (glands and sensory receptors). You will also

learn about some of the common diseases of the skin and way the

skin changes over the normal life span from infancy to old age.

The skin is a complex organ that includes different

tissues and structures whose origins lie within other systems.

Thus its activities must be coordinated with those of other systems,

espcially the circulatory, nervous, and endocrine systems. This

coordination is refered to as integrated functioning, and it enable

the body to maintain a stable internal environment for the healthy

operation of all cells and systems, even when conditions outside

or inside change.

This maintenance of stable internal conditions

is called homeostasis. Homeostasis is a concept that is essential

to understanding the functioning of the human body.

The Skin: An Overview

As the body's outermost covering, the skin

interacts directly with the environment and has several important

functions. Amongst these diverse functions are limits on the entry

and exit of materials, providing sensory awareness of our surroundings,

and the ablity to repair itself upon injury. Clearly the skin

is not merely a passive wall around the body.

- Protection and defense. The skin is an effective barrier against mechanical

injury and the absorption of dangerous chemicals. It blocks penetration

by all but sharp objects. It is the first line of defense against

foreign agents, such as bacteria and viruses, which cause disease.

- Sensation.

The skin is an early warning system for the body. Specialized

sensory organs in the skin continuously monitor the sensations

of touch, pressure, pain, warmth, and cold.

- Water balance.

The outermost layer of the skin contains a water-resistant protein

called keratin. This waterproofing reduces the loss of the body's

precious internal water.

- Temperature regulation and excretion of

wastes. In humans, the skin plays

a direct role in limiting heat loss if the body is too cool and

cooling the body if it becomes too warm. To achieve cooling,

sweat glands secrete water onto the skin. As it evaporates, this

water carries with it heat energy, cools the skin, and lowers

body temperature. The sweat glands also secrete salts and small

amounts of waste products such as urea and ammonia.

- Synthesis of vitamin D. Exposure to the ultraviolet wavelengths of sunlight

causes the skin to produce small quantities of vitamin D which

supplement the smount supplied in the diet. This vitamin is essential

to the contruction of bones and teeth from the minerals calcium

and phosphate.

Tissue

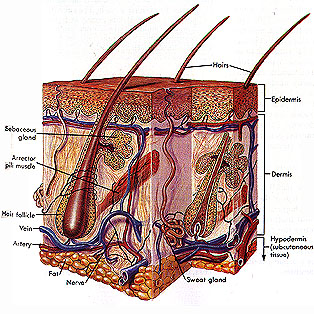

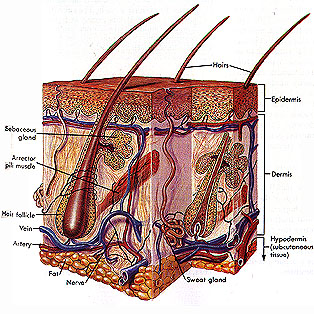

Structure of the Skin

|

Functions of the skin as they were described

above are accomplished by two relatively thin layers of tissue:

an outer epidermis and inner dermis. These are

connected by a thin basement membrane which is somewhat anchored

into the dermis. The thinner epidermis is constructed from stratified

squamous epithelial tissue, while the thicker dermis is a

dense connective tissue. The skin ranges in thickness

from 0.5 mm over the eyelids to 6mm (about 1/4 in.) or more on

areas of the hands and feet that recieve heavy wear and tear.

|

The Epidermis:

a Thin Outer layer.

| The epidermis consists up to

five different layers, or strata. Of the five we will examine

only two layers: the innermost layer called the stratum basale

and the outermost layer, called the stratum corneum. The

epidermis varies in thickness, and all five strata are present

only in thick-skinned areas on the palms and the soles of the

feet. The epidermis constantly undergoes growth and renewal.

In regions of repeated pressure and friction, production of new

cells is stimulated. The skin will formed a callus or corn as

a result of pressure from abnormal wearing, so as you know, the

epidermis can form thick layers to protect the underlying dermis

from abrasion. |

|

New cells are produced by mitoic cell

division in the basal stratum. These

cells are somewhat columnar and upon division, one daughter cell

remains in the basal region, the other migrates towards the surface.

This may take up to 56 days. As the new cells are produced, the

older cells are pushed upward toward the outer surface of the

skin, the cornified stratum.

As these cells move upward, they undergo distinctive

changes, the most significant of which is the synthesis of massive

amounts of the protein keratin, which eventually fills

the cells.The cells that make keratin are called keratinocytes

and account for about 95 percent of all the cells in the epidermis.

Due to keratinization, change shape and eventually die. These

dead squamous cells form the stratum corneum, a layer made of

as many as 25 layers or more. In addition to waterproofing, keratin

contributes great strength and toughnes to the skin and its appendage

structures, the nails and the hair.

The color of the skin, as seen by the appearence

of the outer layer of cells is determined by the thickness of

the stratum corneum, the underlying blood vessels, and the amount

of the brown-black pigment melanin. Melanocytes are a second

type of cell found in the epidermis (stratum basalae). They are

specialized to produce a dark pigment called melanin. These

cells produce and then pass on to other surrounding cells, throughthin

cytoplasmic extensions, the pigment. This process is refered to

as cytocrine secretion. Although regions of the body may

vary in degree of pigmentation, all people have approximatly the

same number of melanocytes, despite racial variation in color.

The amount of melanin produced is determined

by genetic factors, hormones, and exposure to light. Albinism

is a single genetic defect (even though many genes effect pigmentation

production) which prevents pigment production. Hormaonal changes

during pregnancy can lead to a greater amount of pigmentation

to be produced. Increased or decreased blood flow can change the

'pinkness' of the skin, and a decrease in oxygen content can lead

to a blueing of the skin (cyanosis). Carotene is

a yellowis-orange pigment which is lipid soluble and can be stored

in the lipds of the skin. Excessive intake can give the skin an

overly yellowish tint.

Melanin protects the DNA of the dividing cells

in the basal stratum from damage by ultraviolet wavelegnths of

sunlight. Changes in basal cell DNA can lead to skin cancer, and

this melanin screen provides some protection. Skin cancer can

be a serious consequence of extensive exposure to sunlight.

As with all epithelial tissues, the epidermis

contains no blood vessels. Cells in the lower strata can obtain

oxygen and nutriants only by diffusion from the dermis, which

is well supplied with blood vessels. As the cells reach the upper

strata, however, diffusion of nutriants is diminished and the

cells die.

The surface of the skin we admire and care

for consists of dead cells.Each day millions of dead skin cells

are flaked away, to be replaced with new cells from below. Normally

it takes about 4 to 6 weeks for cells to move from the basal stratum

to the cornified stratum, where they are lost. Some estimates

suggest that 80 percent of dust in our homes is actually dead

epidermal cells. Excessive flaking of cells produces dandruff.

The Dermis: the

Deep, Thick layer

The dermis thicker inner layer. The

dermis lies below the epidermis and is substantially thicker than

the epidermis. It is a layer of connective tissue that consists

of an extracellular matrix with abundant collagen, elastic, and

reticular fibers.

The dermis is made of two basic layers: the

upper papillary layer and the deeper reticular layer.

The reticular layer is primarily collagen and elastic fibers and

is responsible for providing the skin with it's strength. Although

collagen fibers lie in a multitude of directions within this layer,

there is a more specific direction that they may lie, dependent

on location. This allows the skin to have a greater flexibility

in directions of common 'stretch'. This orientation causes what

are commonly called cleavage lines. Damage across these lines

such as with excessive stretching or an incision of some sort)

will likely scar; damage with the line will produce little if

any marking.

The papillary region is called such by a series

of projections, papillae, that stretch upward into the

epidermis. These help anchor the demis into the epidermis and

are most numerous in regions with the greatest amount of wear:

the hands and feet. Within the hands and feet, these ridges form

elaborate parallel patterns, increasing friction, providing improved

gripping power. The papillary region also contains numerous blood

vessels to provide the epidermis with nutrients, remove waste,

and help regulate body temperature.

The hair follicle is also found within the

dermis, as are various glands, smooth muscle cells, sensory receptors

and their associated nerves. Vitamin D production occurs in the

dermis, stimulated by the sunlight which passes through the melanin

protection of the epidermis.

The Hypodermis:

the Underlying layer

Beneath the dermis is a layer called Hypodermis

or the Subcutaneous layer. While this is not considered

part of the integumentary system, it helps support the two layers

of the skin by anchoring them to the muscle or bone below. This

layer is made of loose connective tissue, including approximatly

half the bodies fat (adipose), depending upon gender, age,

and heredity. The fibers of the connective tissue is basically

continous with the dermis, so no real, defined boundry exists

between the two. This fat serves as padding for delicate underlying

structures and insulation for retaining body heat. The hypodermis

also allows the skin to easily sllide over bones and joints during

movement. Medically, the hypodermis is the site for the injection

of slow absorbing medications.